Slovenia

| Republic of Slovenia

Republika Slovenija

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: 7th stanza of Zdravljica |

||||||

![Location of �Slovenia��(dark green)–�on the European continent��(bright green &�dark gray)–�in the European Union��(bright green)� —� [Legend]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/250px-EU-Slovenia.svg.png) Location of Slovenia (dark green)

– on the European continent (bright green & dark gray) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

||||||

| Official language(s) | Slovene1 | |||||

| Demonym | Slovenian, Slovene | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Danilo Türk | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Borut Pahor | ||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | Carantania | 7th century | ||||

| - | Joined the Frankish Empire | 745 | ||||

| - | Independence from Austro-Hungarian Empire, forming State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs | October 29, 1918 | ||||

| - | Formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later renamed to Kingdom of Yugoslavia | December 1, 1918 (October 3, 1929) | ||||

| - | Formed Democratic Federal Yugoslavia | November 29, 1943 | ||||

| - | Formed Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, later Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia | January 31, 1946 (7 April 1963) | ||||

| - | Independence from Yugoslavia | June 25, 1991 - Recognised-1992 | ||||

| EU accession | 1 May 2004 | |||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 20,273 km2 (153rd) 7,827 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.6 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2009 estimate | 2,054,199[1] (144th) | ||||

| - | 2002 census | 1,964,036 | ||||

| - | Density | 99.6/km2 (104th) 251/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2009 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $57.741 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $28,118[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2009 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $49.217 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $24,417[2] | ||||

| Gini (2007) | 28.4 (low) | |||||

| HDI (2007) | ||||||

| Currency | Euro (€)3 (EUR) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .si4 | |||||

| Calling code | 386 | |||||

| 1 Italian and Hungarian are recognised as official languages in the residential municipalities of the Italian or Hungarian national community. 2 Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia: Population, Slovenia, 30 June 2008 3 Prior to 2007: Slovenian tolar 4 Also .eu, shared with other European Union member states. |

||||||

Slovenia /sloʊˈviːniə/ sloh-VEE-nee-ə, officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: Republika Slovenija, [reˈpublika sloˈveːnija] ), is a country in Central Europe touching the Alps and bordering the Mediterranean. Slovenia borders Italy on the west, the Adriatic Sea on the southwest, Croatia on the south and east, Hungary on the northeast, and Austria on the north. The capital and largest city of Slovenia is Ljubljana.

Slovenia covers an area of 20,273 square kilometres and has a population of 2.06 million. Around 40% of Slovenia's land mass is elevated land—mostly in the form of mountains and plateaus—which is located in the interior regions of the country. The highest point of Slovenia is the 2,864 metre (9,396 ft) high Mount Triglav. The majority of the population speaks Slovene, which is also the country's official language. Other local official languages are Hungarian and Italian.

Slovenia is a member of the European Union, the Eurozone, the Schengen area, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Council of Europe, NATO, UNESCO, WTO, OECD and UN. Per capita, it is the richest Slavic nation-state, and is 85.5% of the EU27 average GDP (PPP) per capita.

History

Although a distinct Slovene identity was first articulated in the 16th century, and its prehistory can be traced back to the 8th century,[3] Slovenia itself is a relatively modern political entity. The notion of Slovenia first emerged in the 19th Century with the idea of United Slovenia, an autonomous kingdom within the Habsburg Monarchy that would unite all Slovene Lands around the Duchy of Carniola, the central Slovene-populated imperial crownland. It became a reality only after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918, when Slovenia became a de facto self-governing entity within the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, which it helped to create. Slovenian autonomy was later abolished with the constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes of 1921, and although Slovenia proper managed to regain territorial integrity in 1931 as the Drava Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, it did not enjoy actual autonomy, and the name itself was not officially in use. Slovenia became an autonomous political entity after World War II, as a full-scale republic, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Its current borders were finalized in 1954, with the abolition of the Free Territory of Trieste and the official annexation of the Koper district of the so-called Zone B of the Free Territory to Yugoslavia, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Osimo in 1975.

During its history, the current territory of Slovenia was part of many different state formations, including the Roman Empire, the Frankish Kingdom, the Holy Roman Empire, the Republic of Venice (only some western areas), the Habsburg Monarchy, and the First French Empire (only its western part). In 1918, the Slovenes exercised self-determination for the first time by co-founding the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, with their western territories remaining in the Kingdom of Italy. During World War Two, Slovenia was occupied and annexed by Germany, Italy and Hungary, only to emerge afterwards reunified with its western part (Slovenian Littoral) as a founding member of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, before declaring full sovereignty in 1991.

Prehistory

The oldest signs of human settlement in present-day Slovenia were found in the Jama Cave in the Loza Woods near Orehek in Inner Carniola, where two stone tools approximately 250,000 years old were recovered. During the last glacial period, present-day Slovenia was inhabited by Neanderthals; the most famous Neanderthal archeological site in Slovenia is a cave close to the village of Šebrelje near Cerkno, where the Divje Babe flute, the oldest known musical instrument in the world was found in 1995. In the transition period between the Bronze age to the Iron age, the Urnfield culture flourished. Numerous archeological remains dating from the Hallstatt period have been found in Slovenia, with important settlements in Most na Soči, Vače, and Šentvid pri Stični.

Ancient times

In the Iron Age, present-day Slovenia was inhabited by the Illyrian, Celtic and Venetic tribes until the 1st Century BC., when the Romans conquered the region establishing the provinces of Pannonia and Noricum. What is now western Slovenia was included directly under Roman Italia as part of the X region Venetia et Histria. Important Roman towns located in present-day Slovenia included Emona, Celeia and Poetovio. Other important settlements were Nauportus, Neviodunum, Haliaetum, Atrans, and Stridon.

During the migration period, the region suffered invasions of many barbarian armies, due to its strategic position as the main passage from the Pannonian plain to the Italian peninsula. Rome finally abandoned the region at the end of the 4th Century. Most cities were destroyed, while the remaining local population moved to the highland areas, establishing fortified towns. In the 5th century, the region was part of the Ostrogothic kingdom, and was later contested between the Ostrogoths, the Byzantine Empire and the Lombards.

The Middle Ages

Slavic ancestors of the present-day Slovenes settled in the East Alpine area in the 6th century. These Slavic tribes, known as the Alpine Slavs, were submitted to Avar rule before joining the Slavic chieftain Samo's Slavic tribal union in 623 AD. After Samo's death, the Slavs of Carniola (in present-day Slovenia) again fell to Avar rule, while the Slavs north of the Karavanke range (in present-day Austrian regions of Carinthia, Styria and East Tyrol) established the independent principality of Carantania. In 745, Carantania and the rest of Slavic-populated territories of present-day Slovenia were incorporated into the Carolingian Empire, while Carantanians and other Slavs living in present Slovenia converted to Christianity.

Carantania retained its internal independence until 828 when the local princes were deposed following the anti-Frankish rebellion of Ljudevit Posavski and replaced by a Germanic (primarily Bavarian) ascendancy. Under Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia, Carantania, now ruled by a mixed Bavarian-Slav nobility, shortly emerged as a regional power, but was destroyed by the Hungarian invasions in the late 9th century.

Carantania-Carinthia was established again as an autonomous administrative unit in 976, when Emperor Otto I, "the Great", after deposing the Duke of Bavaria, Henry II, "the Quarreller", split the lands held by him and made Carinthia the sixth duchy of the Holy Roman Empire, but old Carantania never developed into a unified realm.

The first mentions of a common Slovene ethnic identity, transcending regional boundaries, date from the 16th century.[4]

During the 14th century, most of the Slovene Lands passed under the Habsburg rule. In the 15th century, the Habsburg domination was challenged by the Counts of Celje, but by the end of the century the great majority of Slovene-inhabited territories were incorporated into the Habsburg Monarchy. Most Slovenes lived in the administrative region known as Inner Austria, forming the majority of the population of the Duchy of Carniola and the County of Gorizia and Gradisca, as well as of Lower Styria and southern Carinthia.

Slovenes also inhabited most of the territory of the Imperial Free City of Trieste, although representing the minority of its population.[5]

Early Modern Period

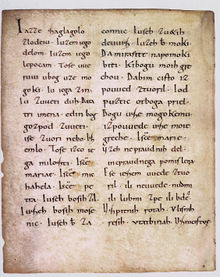

In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation spread throughout the Slovene Lands. During this period, the first books in the Slovene language were written by the Protestant preacher Primož Trubar and his followers, establishing the base for the development of the standard Slovene language. In the second half of the 16th century, numerous books were printed in Slovene, including an integral translation of the Bible by Jurij Dalmatin.

Although almost all Protestants were expelled from the Slovene Lands (with the exception of Prekmurje) by the beginning of the 17th century, they left a strong legacy in the tradition of Slovene culture, which was partially incorporated in the Catholic Counter-Reformation in the 17th century. The old Slovene orthography, also known as Bohorič's Alphabet, which was developed by the Protestants in the 16th century and remained in use until mid 19th century, testified to the unbroken tradition of Slovene culture as established in the years of the Protestant Reformation.

Between the 15th and the 17th century, the Slovene Lands suffered many calamities. Many areas, especially in southern Slovenia, were devastated by the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars. Many flourishing towns, like Vipavski Križ and Kostanjevica na Krki, were completely destroyed by incursions of the Ottoman Army, and never recovered. The nobility of the Slovene-inhabited provinces had an important role in the fight against the Ottoman Empire. The Carniolan noblemen's army thus defeated the Ottomans in the Battle of Sisak of 1593, marking the end of the immediate Ottoman threat to the Slovene Lands, although sporadic Ottoman incursions continued well into the 17th century.

.jpg)

In the 16th and 17th century, the western Slovene regions became the battlefield of the wars between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Venetian Republic, most notably the War of Gradisca, which was largely fought in the Slovene Goriška region. Between late 15th and early 18th century, the Slovene lands also witnessed many peasant wars, most famous being the Carinthian peasant revolt of 1478, the Slovene peasant revolt of 1515, the Croatian-Slovenian peasant revolt of 1573, the Second Slovene peasant revolt of 1635, and the Tolmin peasant revolt of 1713.

Late 17th century was also marked by a vivid intellectual and artistic activity. Many Italian Baroque artists, mostly architects and musicians, settled in the Slovene Lands, and contributed greatly to the development of the local culture. Scientists like Janez Vajkard Valvasor contributed to the development of the scholarly activities. In 1693, the first academy on Slovene soil, the Academia operosorum Labacensis, was established. By the early 18th century, however, the region entered another period of stagnation, which was slowly overcome only by mid 18th century.

Enlightened Absolutism to the rise of the national movement

Between early 18th century and early 19th century, the Slovene lands experienced a period of peace, with a moderate economic recovery starting from mid 18th century onward. The Adriatic town of Trieste was declared a free port in 1718, boosting the economic activity throughout the western parts of the Slovene Lands. The political, administrative and economic reforms of the Habsburg rulers Maria Theresa of Austria and Joseph II improved the economic situation of the peasantry, and were well received by the emerging bourgeoisie, which was however still weak.

In the late 18th century, a process of standardarization of Slovene language began, promoted by Carniolan clergymen like Marko Pohlin and Jurij Japelj. During the same period, peasant-writers began using and promoting the Slovene vernacular in the countryside. This popular movement, known as bukovniki, started among Carinthian Slovenes as part a wider revival of Slovene literature. The Slovene cultural tradition was strongly reinforced in the Enlightenment period in the 18th century by the endeavours of the Zois Circle. After two centuries of stagnation, Slovene literature emerged again, most notably in the works of the playwright Anton Tomaž Linhart and the poet Valentin Vodnik. However, German remained the main language of culture, administration and education well into the 19th century.

After a short French interim between 1805 and 1813, all Slovene Lands were included in the Austrian Empire. Slowly, a distinct Slovene national consciousness developed, and the quest for a political unification of all Slovenes became widespread. In the 1820s and 1840s, the interest in Slovene language and folklore grew enormously, with numerous many philologists collecting folk songs and advancing the first steps towards a standardization of the language. A small number of Slovene activist, mostly from Styria and Carinthia, embraced the Illyrian movement that started in neighboring Croatia and aimed at uniting all South Slavic peoples. Pan-Slavic and Austro-Slavic ideas also gained importance. However, the intellectual circle around the philologist Matija Čop and the Romantic poet France Prešeren was influential in affirming the idea of Slovene linguistic and cultural individuality, refusing the idea of merging the Slovenes into a wider Slavic nation.

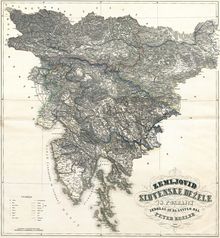

In 1848, a mass political and popular movement for the United Slovenia (Zedinjena Slovenija) emerged as part of the Spring of Nations movement within the Austrian Empire. Slovene activists demanded a unification of all Slovene-speaking territories in a unified and autonomous Slovene kingdom within the Austrian Empire. Although the project failed, it served as an almost undisputed platform of Slovene political activity in the following decades.

Clashing nationalisms in late 19th century

Between 1848 and 1918, numerous institutions (including theatres and publishing houses, as well as political, financial and cultural organisations) were founded in the so-called Slovene National Awakening. Despite their political and institutional fragmentation and lack of proper political representation, the Slovenes were able to establish a functioning national infrastructure.

With the introduction of a constitution granting civil and political liberties in the Austrian Empire in 1860, the Slovene national movement gained force. Despite its internal differentiation among the conservative Old Slovenes and the progressive Young Slovenes, the Slovene nationals defended similar programs, calling for a cultural and political autonomy of the Slovene people. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, a series of mass rallies called tabori, modeled on the Irish monster meetings, were organized in support of the United Slovenia program. These rallies, attended by thousands of people, proved the allegiance of wider strata of the Slovene population to the ideas of national emancipation.

By the end of the 19th century, Slovenes had established a standardized literary language, and a thriving civil society. Literacy levels were among the highest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and numerous national associations were present at grassroots level. The idea of a common political entity of all South Slavs, known as Yugoslavia, emerged.

Since the 1880s, a fierce culture war between Catholic traditionalists and intergalists on one side, and liberals, progressivists and anticlericals dominated Slovene political and public life, especially in Carniola. During the same period, the growth of industrialization intensified social tensions. Both Socialist and Christian socialist movements mobilized the masses. In 1905, the first Socialist mayor in the Austro-Hungarian Empire was elected in the Slovene mining town of Idrija on the list of the Yugoslav Social Democratic Party. In the same years, the Christian socialist activist Janez Evangelist Krek organized hundreds of workers and agricultural cooperatives throughout the Slovene countryside.

At the turn of the century, national struggles in ethnically mixed areas (especially in Carinthia, Trieste and in Lower Styrian towns) dominated the political and social lives of the citizenry. By the 1910s, the national struggles between Slovene and German speakers (and, in the Austrian Littoral, Italian speakers) overshadowed other political conflicts and brought about a nationalist radicalization on both sides.

In the last two decades before World War One, Slovene arts and literature experienced one of its most flourishing periods, with numerous talented modernist authors, painters and architects. The most important authors of this period were Ivan Cankar and Oton Župančič, while Ivan Grohar and Rihard Jakopič were among the most talented Slovene visual artists of the time.

In the late 19th century, the town of Ljubljana, the capital of Carniola, emerged as the undisputed centre of all Slovene Lands. After the Ljubljana earthquake of 1895, the town experienced a rapid modernization under the charismatic Liberal nationalist mayors Ivan Hribar and Ivan Tavčar. Architects like Max Fabiani and Ciril Metod Koch introduced their own version of the Vienna Secession architecture to Ljubljana. In the same period, the Adriatic port of Trieste became an increasingly important center of Slovene economy, culture and politics. By 1910, around a third of the city population was Slovene, and the number of Slovenes in Trieste was higher than in Ljubljana.

At the turn of the century, hundreds of thousands of Slovenes emigrated to other countries, mostly to the United States, but also to South America, Germany, Egypt, and to larger cities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, especially Zagreb and Vienna. It has been calculated that around 300,000 Slovenes emigrated between 1880 and 1910, which means the one in six Slovenes left their homeland. Such disproportionally high emigration rates resulted in a relatively small population growth in the Slovene Lands. Comparatively to other Central European regions, the Slovene Lands lost demographic weight between the late 18th and early 20th century.

World War One and the Creation of Yugoslavia

After the outbreak of World War I, the Austrian Parliament was dissolved and civil liberties suspended. Many Slovene political activists, especially in Carniola and Styria, were imprisoned by Austro-Hungarian authorities on charges of pro-Serbian or pan-slavic sympathies. 469 Slovenes were executed on charges of treason in the first year of the war alone, provoking a strong anti-Austrian resentment among the national-minded strata of the Slovene population. Hundreds of thousands of Slovene conscripts were drafted in the Austro-Hungarian Army, and over 30,000 of them lost their lives in the course of the war.

In May 1915, the fighting started on Slovene soil, as well. Italy entered the conflict after the western allies had supported its territorial expansion at the expense of Austria-Hungary. In the Treaty of London of 1915, the Slovenian Littoral and some western districts of Carniola were promised to Italy after the war. The Italian Royal Army launched an attack on Austria-Hungary in 1915, thus opening the Italian front. Some of the fiercest battles were fought along the Soča (Isonzo) river and on the Kras (Carso) plateau in what is now western Slovenia. Entire areas of the Slovenian Littoral were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of Slovenes were resettled as refugees in parts of Austria and Italy. While the situation in the Austrian refugee camps were relatively good, Slovene refugees in Italian camps were treated as state enemies, and several thousands died of malnutrition and diseases between 1915 and 1918.[6]

In 1917, after the Battle of Caporetto ended the fighting on Austro-Hungarian (Slovenian) soil, the political life in Austria-Hungary resumed. The Slovene People's Party launched a movement for self-determination, demanding the creation of a semi-independent South Slavic state under Habsburg rule. The proposal was picked up by most Slovene parties, and a mass mobilization of Slovene civil society, known as the Declaration Movement, followed. By early 1918, more than 200,000 signatures were collected in favor of the Slovene People Party's proposal.[7]

During the War, some 500 Slovenes served as volunteers in the Serbian army, while a smaller group led by Captain Ljudevit Pivko, served as volunteers in the Italian Army. In the final year of the war, many predominantly Slovene regiments in the Austro-Hungarian Army staged a mutiny against their military leadership; the most famous mutiny of Slovene soldiers was the Judenburg Rebellion in May 1918.[8]

With the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in October 1918, the Slovenes formed the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, which soon merged with Serbia and Montenegro into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The western parts of the Slovene Lands (the Slovenian Littoral and western districts of Inner Carniola) were occupied by the Italian Army, and officially annexed to the Kingdom of Italy with the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920.[9]

After the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in late 1918, an armed dispute started between the Slovenes and German Austria for the regions of Lower Styria and southern Carinthia. In November 1918, the Slovene general Rudolf Maister seized the city of Maribor, while a group of volunteers led by Franjo Malgaj attempted to take control of southern Carithia. Fighting in Carinthia lasted between December 1918 and June 1919, when the Slovene volunteers and the regular Serbian Army managed to occupy the city of Klagenfurt. In compliance with the Treaty of Saint-Germain, the Yugoslav forces had to withdraw from Klagenfurt, while a referendum was to be held in other areas of southern Caritnthia. In October 1920, the majority of the population of souther Carinthia voted to remain in Austria, and only a small portion of the province (around Dravograd and Guštanj) was awarded to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. With the Treaty of Trianon, however, Yugoslavia was awarded the Slovene-inhabited Prekmurje region, which used to belong to Hungary since the 10th century, and had little connections with the rest of the Slovene Lands.

The interwar period

In 1921, a centralist constitution was passed in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes against the vote of the great majority (70%) of Slovene MPs. Despite the centralist policies of the Yugoslav kingdom, Slovenes managed to maintain a high level of cultural autonomy, and both economy and the arts prospered. Slovene politicians participated in almost all Yugoslav governments, and the Slovene conservative leader Anton Korošec briefly served as the only non-Serbian Prime Minister of Yugoslavia in the period between the two world wars.

On the other hand, Slovenes in Italy, Austria and Hungary, became victims of policies of State policies of forced assimilation and sometimes violent persecution. The Slovenian Littoral was annexed to Italy and included in the Julian March administrative region. Between 1918 and 1922, several violent actions were directed against the Slovene communities in Italy, both by the mob and by ultra-nationalist militias. After 1922, a policy of violent Fascist Italianization was implemented, triggering the reaction of local Slovenes and Istrian Croats. In 1927, the militant anti-Fascist organization TIGR (an acronym for the place-names Trieste, Istria, Gorizia, and Rijeka) was founded. Between 1922 and 1941, more than 70,000 Slovenes fled from the Italian Julian March, mostly to Yugoslavia, but also to Argentina and other South American countries.

In 1929, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was renamed to Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The constitution was abolished, civil liberties suspended, while the centralist pressure intensified. Slovenia was renamed to Drava Banovina. During the whole interwar period, Slovene voters strongly supported the conservative Slovene People's Party, which unsuccessfully fought for the autonomy of Slovenia within a federalized Yugoslavia. In 1935, however, the Slovene People's Party joined the pro-regime Yugoslav Radical Community, opening the space for the development of a left wing autonomist movement. In the 1930s, the economic crisis created a fertile ground for the rising of both leftist and rightist radicalisms. In 1937, the Communist Party of Slovenia was founded as an autonomous party within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. Between 1938 and 1941, left liberal, Christian left and agrarian forces established close relations with members of the illegal Communist party, aiming at establishing a broad anti-Fascist coalition.

After 1918, Slovenia became one of the main industrial centers of Yugoslavia. Already in 1919, the industrial production in Slovenia was four times greater than in Serbia, and twenty-two times greater than in Yugoslav Macedonia. The interwar period brought a further industrialization in Slovenia, with a rapid economic growth in the 1920s followed by a relatively successful economic adjustment to the 1929 economic crisis. This development however affected only certain areas, especially the Ljubljana Basin, the Zasavje region, parts of Slovenian Carinthia, and the urban areas around Celje and Maribor. Tourism experienced a period of great expansion, with resort areas like Bled and Rogaška Slatina gaining a an international reputation. Elsewhere, agriculture and forestry remained the predominant economic activities. Nevertheless, Slovenia emerged as one of the most prosperous and economically dynamic areas in Yugoslavia, profiting from a large Balkanic market. Arts and literature also prospered, as did architecture. The two largest Slovenian cities, Ljubljana and Maribor, underwent an extensive program of urban renewal and modernization. Architects like Jože Plečnik, Ivan Vurnik and Vladimir Šubic introduced modernist architecture to Slovenia.

World War Two

On 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis Powers. Slovenia was divided among the occupying powers: Fascist Italy occupied southern Slovenia (Lower Carniola, Inner Carniola and Ljubljana), Nazi Germany got northern and eastern Slovenia (Upper Carniola, Slovenian Styria, Slovenian Carinthia and Posavje), while Horthy's Hungary was awarded the Prekmurje region. Some villages in south-eastern Slovenia were annexed by the Independent State of Croatia.

While the Italians gave Slovenes a cultural autonomy within their occupation zone (the Province of Ljubljana), the Nazis started a policy of violent Germanisation, which culminated with the resettlement more than 83,000 Slovenes to other parts of the Third Reich, as well as to Serbia and Croatia. Already in the summer of 1941, a liberation movement under the Communist leadership emerged.

Due to political assassinations carried out by the Communist squads, as well as the pre-existing radical anti-Communism of the conservative circles of the Slovenian society, a civil war between Slovenes broke out in the Italian-occupied south-eastern Slovenia (known as Province of Ljubljana) in spring of 1942. The two fighting factions were the Liberation Front of the Slovenian People and the Axis-sponsored anti-communist militia, the Slovene Home Guard, initially formed by local anti-Communist activists in order to protect villages from partisans' incursions.

The Slovene partisan guerrillas managed to liberate large portions of the Slovene lands, contributing to the defeat of Nazism. As a result of the war the vast majority of the native ethnic German population were either forcefully expelled or fled to neighboring Austria. Immediately after the war, some 12,000 members of the Slovene Home Guard were killed in the area of the Kočevski Rog, while thousands of anti-communists civilians were killed in the first year after the war, many of them in concentration camps of Teharje and Šterntal.[10]

These massacres were silenced, and remained a taboo topic until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when dissident intellectuals brought it to public discussion. In addition, hundreds (some say thousands) of ethnic Italians from Istria and Trieste were killed by the Yugoslav Army and partisan forces in the Foibe massacres, while some 27,000 of them fled Slovenia from Communist persecution in the so-called Istrian exodus. The overall number of World War Two casualties in Slovenia is estimated to 89,000, while 14,000 people were killed immediately after the end of the war.[10] The overall number of WWII casualties in Slovenia was thus of around 7,2% of the pre-war population, which is above the Yugoslav average, and among the highest percentages in Europe.

The Communist period

Following the re-establishment of Yugoslavia at the end of World War II, Slovenia became part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, declared on 29 November 1943. A socialist state was established, but because of the Tito-Stalin split, economic and personal freedoms were broader than in the Eastern Bloc. In 1947, Italy ceded most of the Julian March to Yugoslavia, and Slovenia thus regained the Slovenian Littoral.

The dispute over the port of Trieste however remained opened until 1954, until the short-lived Free Territory of Trieste was divided among Italy and Yugoslavia, thus giving Slovenia access to the sea. This division was ratified only in 1975 with the Treaty of Osimo, which gave a final legal sanction to Slovenia's long disputed western border. From the 1950s, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia enjoyed a relatively wide autonomy.

Between 1945 and 1948, a wave of political repressions took place in Slovenia and in Yugoslavia. Thousands of people were imprisoned for their political beliefs. Several tens of thousands of Slovenes left Slovenia immediately after the war in fear of Communist persecution. Many of them settled in Argentina, which became the core of Slovenian anti-Communist emigration. More than 50,000 more followed in the next decade, frequently for economic reasons, as well as political ones. These later waves of Slovene immigrants mostly settled in Canada and in Australia, but also in other western countries.

In 1948, the Tito-Stalin split took place. In the first years following the split, the political repression worsened, as it extended to Communists accused of Stalinism. Hundreds of Slovenes were imprisoned in the concentration camp of Goli Otok, together with thousands of people of other nationalities. Among the show trials that took place in Slovenia between 1945 and 1950, the most important were the Nagode trial against democratic intellectuals and left liberal activists (1946) and the Dachau trials (1947–1949), where former inmates of Nazi concentration camps were accused of collaboration with the Nazis. Many members of the Roman Catholic clergy suffered persecution. The case of bishop of Ljubljana Anton Vovk, who was doused with gasoline and set on fire by Communist activists during a pastoral visit to Novo Mesto in January 1952, echoed in the western press.

Between 1949 and 1953, a forced collectivization was attempted. After its failure, a policy of gradual liberalization was followed. A new economic policy, known as workers self-management started to be implemented under the advice and supervision of the main theorist of the Yugoslav Communist Party, the Slovene Edvard Kardelj.

In the late 1950s, Slovenia was the first of the Yugoslav republics to begin a process of relative pluralization. A decade of fervent cultural and literary production followed, with many tensions between the regime and the dissident intellectuals. By the late 1960s, the reformist fraction gained control of the Slovenian Communist Party, launching a series of reforms, aiming at the modernization of Slovenian society and economy. In 1973, this trend was stopped by the conservative fraction of the Slovenian Communist Party, backed by the Yugoslav Federal government. A period known as the "years of lead" (Slovene: svinčena leta) followed.

From the late 1950s onward, dissident circles started to be formed, mostly around short-lived independent journals, such as Revija 57 (1957–1958), which was the first independent intellectual journal in Yugoslavia and one of the first of this kind in the Communist bloc,[11] and Perspektive (1960–1964). Among the most important critical public intellectuals in this period were the sociologist Jože Pučnik, the poet Edvard Kocbek, and the literary historian Dušan Pirjevec.

In the 1980s, Slovenia experienced a rise of cultural pluralism. Numerous grass-roots political, artistic and intellectual movements emerged, including the Neue Slowenische Kunst, the Ljubljana school of psychoanalysis, and the Nova revija intellectual circle. By the mid 1980s, a reformist fraction, led by Milan Kučan, took control of the Slovenian Communist Party, starting a gradual reform towards a market socialism and controlled political pluralism.

The Yugoslav economic crisis of the 1980s increased the struggles within the Yugoslav Communist regime regarding the appropriate economic measures to be undertaken. Slovenia, which had less than 10% of overall Yugoslav population, produced around a fifth of the country's GDP and a fourth of all Yugoslav exports. The political disputes around economic measures was echoed in the public sentiment, as many Slovenes felt they were being economically exploited, having to sustain an expensive and inefficient federal administration.

Democratic changes and the gain of independence

In 1987 and 1988, a series of clashes between the emerging civil society and the Communist regime culminated with the so-called Slovenian Spring. A mass democratic movement, coordinated by the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, pushed the Communists in the direction of democratic reforms. These revolutionary events in Slovenia pre-dated by almost one year the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe, but went largely unnoticed by the international observers.

At the same time, the confrontation between the Slovenian Communists and the Serbian Communist Party, dominated by the charismatic nationalist leader Slobodan Milošević, became the most important political struggle in Yugoslavia. Bad economic performance of the Federation, and the rising clashes between the different republics, created a fertile soil for the rise of secessionist ideas among Slovenes, both anti-Communists and Communists. In January 1990, the Slovenian Communists left the Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in protest against the domination of the Serb nationalist leadership, thus effectively dissolving the Yugoslav Communist Party, the only remaining institution holding the country together.

In April 1990, the first free and democratic elections were held, and the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia defeated the former Communist party. A coalition government led by the Christian Democrat Lojze Peterle was formed, and began economic and political reforms that established a market economy and a liberal democratic political system. At the same time, the government pursued the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. In December 1990, a referendum on the independence of Slovenia was held, in which the overwhelming majority of Slovenian residents (around 89%) voted for the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. Independence was declared on 25 June 1991. A short Ten-Day War followed, in which the Slovenian forces successfully rejected Yugoslav military interference.

After 1990, a stable democratic system evolved, with economic liberalization and gradual growth of prosperity. Slovenia joined NATO on 29 March 2004 and the European Union on 1 May 2004. Slovenia was the first post-Communist country to hold the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, for the first six months of 2008.

Politics

As a young independent republic, Slovenia pursued economic stabilisation and further political openness, while emphasising its Western outlook and Central European heritage. Today, with a growing regional profile, a participant in the SFOR peacekeeping deployment in Bosnia-Hercegovina and the KFOR deployment in Kosovo, and a charter World Trade Organization member, Slovenia plays a role on the world stage quite out of proportion to its small size.

The Slovenian head of state is the president, who is elected by popular vote every five years, and has mainly advisory and ceremonial duties. The executive branch is headed by the prime minister and the council of ministers or cabinet, who are elected by the National Assembly.

The bicameral Parliament of Slovenia is characterised by an asymmetric duality, as the Constitution does not accord equal powers to both chambers. The bulk of the power is concentrated in the National Assembly (Državni zbor), while the National Council (Državni svet) only has a very limited advisory and control powers. The National Assembly has ninety members, 88 of which are elected by all the citizens in a system of proportional representation, while two are elected by the registered members of the autochthonous Hungarian and Italian minorities.

Elections take place every four years. The National Assembly is the supreme representative and legislative institution, exercising legislative and electoral powers as well as control over the Executive and the Judiciary. The National Council has forty members, appointed to represent social, economic, professional and local interest groups. Among its most important powers is the "postponing veto" — the National Council return a bill to the National Assembly for further discussion. The veto can be overrun by the National Assembly a majority vote.

The government, like most of the Slovenian polity, shares a common view of the desirability of a close association with the West, specifically of membership in both the European Union and NATO.

.jpg)

Between 1992 and 2004, the Slovenian political scene was characterized by the rule of the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia, which carried out much of the economic and political transformation of the country. The party's president Janez Drnovšek, who served as Prime Minister between 1992 and 2002, was the one of the most influential Slovenian politician of the 1990s, together with the Slovenian President Milan Kučan (served between 1990 and 2002), who was credited for the peaceful transition from Communism to democracy.

Throughout this period, a policy of relative consensus between left and right wing political parties was followed, favouring grand coalitions over single-party governments. Nevertheless, several serious clashes occurred between left wing and right wing parties in the 1990s, with many corruption scandals, as well as scandals involving secret services, the interference of the army in the civil sphere, and arms trafficking. The relationship between the State and the Roman Catholic Church was also an important political issue in the 1990s, and has remained a source of controversy.

In 2004, the ruling Liberal Democracy suffered a severe defeat that brought the liberal conservative Slovenian Democratic Party to power. Between 2004 and 2007, the Liberal Democracy lost much of its influence due to internal struggles, enabling the rise of the left wing Social Democrats as the main opposition force to the center-right government of Janez Janša. In 2008, the left wing coalition headed by the Social Democrat Borut Pahor won the elections by a narrow margin. Since 2004, Slovenia has been moving towards a two-party system, with the Slovenian Democratic Party and the Social Democrats as two major political forces.

On the general level, the Slovenian left tends to favor a strong welfare state over economic freedom and is often characterized by protectionist policies towards nationally owned business, while the right wing stresses economic freedom and follows more friendly policies towards foreign investments. Regarding social policies, the left tends to be more inclusive towards immigrants and ethnic and social minorities, while being rather critical to the role of the Roman Catholic Church in public life. The right wing, on the other hand, is more socially conservative and more in favour of religious communities, especially the Catholic Church.

Issues such as the relations between public and private education, the role of private enterprise in public health care and the regionalization of the country have been important divisive issues in the past years. In general, the right wing parties draw most of their support from eastern and northern Slovenia, and from rural areas and smaller towns throughout the country, while the left wing is stronger in the west, in the industrialized towns throughout the country, and in bigger urban centers, especially in Ljubljana.

Despite apparent bitterness that divides the left and right forces in contemporary Slovenia, much of which derives from a different stand towards the Communist past, there are few fundamental philosophical differences between them in the area of public policy. Slovenian society is built on consensus, which has converged on a social-democrat model of welfare state. Political differences tend to be rooted in the roles that groups and individuals played during the years of Communist rule, and during the struggle for independence and democracy in the 1980s, rather than in radically different economic policies.

Unlike many other former Communist countries, Slovenia pursued internal economic restructuring with caution, giving a clear preference to an approach of gradual economic transformation, and rejecting shock therapies. The first phase of privatisation (socially owned property under the SFRY system) is now complete, and sales of remaining large state holdings are planned for next year. Trade has been diversified toward the West (trade with EU countries make up 66% of total trade in 2000) and the growing markets of central and eastern Europe. Manufacturing accounts for most employment, with machinery and other manufactured products comprising the major exports. The economy provides citizens with a good standard of living.

Administrative divisions

The traditional regions of Slovenia based on the former four Habsburg crown lands (Carniola, Carinthia, Styria, and the Littoral) are the following:

| English name | Native name | Largest city | |

| Slovenian Littoral | Primorska | Koper | |

| Upper Carniola | Gorenjska | Ljubljana | |

| Inner Carniola | Notranjska | Postojna | |

| Lower Carniola | Dolenjska | Novo Mesto | |

| Carinthia | Koroška | Ravne na Koroškem | |

| Lower Styria | Štajerska | Maribor | |

| Prekmurje | Prekmurje | Murska Sobota |

Statistical regions

The two macroregions are:

- East Slovenia (Vzhodna Slovenija - SI01), which groups the regions of Pomurska, Podravska, Koroška, Savinjska, Zasavska, Spodnjeposavska, Jugovzhodna Slovenija and Notranjsko-kraška.

- West Slovenia (Zahodna Slovenija - SI02), which groups the regions of Osrednjeslovenska, Gorenjska, Goriška and Obalno-kraška.

Municipalities

Slovenia is divided into 210 local municipalities, eleven of which have urban status.

Tourism

Slovenia offers tourists a wide variety of landscapes in a small space: Alpine in the northwest, Mediterranean in the southwest, Pannonian in the northeast and Dinaric in the southeast.

The nation's capital, Ljubljana, has many important Baroque and Vienna Secession buildings, with several important works of the native born architect Jože Plečnik. Other attractions include the Julian Alps with picturesque Lake Bled and the Soča Valley, as well as the nation's highest peak, Mount Triglav. Perhaps even more famous is Slovenia's karst named after the Karst Plateau in the Slovenian Littoral. More than 28 million visitors have visited the Postojna Cave, while a 15-minute ride from it are the Škocjan Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Several other caves are open to public, including the Vilenica Cave (the oldest show cave in Europe and the venue of an annual literary festival).

Further in the same direction is the Adriatic coast in Slovenian Istria, where the most important historical monument is the Venetian Gothic Mediterranean town of Piran. The former fishermen town of Izola has also been transformed into a popular tourist destination; many tourists also appreciate the old Medieval center of the port of Koper, which is however less popular among tourists than the other two Slovenian coastal towns.

The hills around Slovenia's second-largest city, Maribor, are renowned for their wine-making. Even though Slovenes tend to consume most of the wine they produce, some brands like Ljutomer have made their appearance abroad. The northeastern part of the country is rich with spas, with Rogaška Slatina being perhaps its most prominent site. Spa tourism has grown in importance in the last two decades, attracting many German, Austrian, Italian and Russian visitors. Important spas in Slovenia include Radenci, Čatež ob Savi, Dobrna, and Moravske Toplice.

Rural tourism is important throughout the country, and it is especially developed in the Kras region, parts of Inner Carniola, Lower Carniola and Slovenian Istria, and in the area around Podčetrtek and Kozje in eastern Styria. Horse-riding, cycling and hiking are among the most important tourist activities in these areas.

Triglav National Park (Slovene: Triglavski narodni park) is a national park located in Slovenia. It was named after Mount Triglav, a national symbol of Slovenia. Triglav is situated almost in the middle of the national park. From it the valleys spread out radially, supplying water to two large river systems having their sources in the Julian Alps: the Soča and the Sava, flowing to the Adriatic and Black Sea, respectively.

Gambling tourism is very important in Slovenia. Slovenia is the country with the highest percentage of casinos per 1,000 inhabitants in the European Union. The casino Perla in Nova Gorica is considered the largest casino in Europe.[12] Other important casinos include the Hotel Park casino in Nova Gorica, the Portorož casino, and the Bled casino. Several smaller gambling places exist in Slovenia, especially in the Goriška region.

The proposal for conservation dates back to the year 1908, and was realised in 1924. Then, on the initiative taken by the Nature Protection Section of the Slovene Museum Society together with the Slovene Mountaineering Society, a twenty year lease was taken out on the Triglav Lakes Valley area, some 14 km². It was destined to become an Alpine Protection Park, however permanent conservation was not possible at that time.In 1961, after many years of effort, the protection was renewed (this time on a permanent basis) and somewhat enlarged, embracing around 20 km². The protected area was officially designated as the Triglav National Park. Under this act, however, all objectives of a true national park were not attained and for this reason over the next two decades, new proposals for the extension and rearrangement of the protection were put forward. Finally, in 1981, a rearrangement was achieved and the park was given a new concept and enlarged to 838 km² – the area it continues to cover to this day.

The Karavanke mountain range and the Kamnik Alps are also important tourist destinations, as are the Pohorje mountains. Unlike the Julian Alps, however, these areas seem to attract mostly Slovene visitors and visitor from the neighboring regions of Austria, and remain largely unknown to tourists from other countries. The biggest exception is the Logar Valley, which has been promoted heavily since the 1980s.

Slovenia has a number of smaller Medieval towns, which serve as important tourist attractions. Among them, the most famous are Ptuj, Škofja Loka and Piran. Fortified villages, mostly located in western Slovenia (Štanjel, Vipavski Križ, Šmartno), have become an important tourist destination, as well, especially due to the cultural events organized in their scenic environments.

An important attraction are Slovenia's many castles and medieval fortresses, although many have been destroyed in World War Two and only a few have been renovated. The most popular tourist sights among Slovenian castles are the Predjama Castle near Postojna, the Bled Castle, the Snežnik Castle, and the Otočec Castle near Novo Mesto.

Geography

Slovenia is situated in Central Europe touching the Alps and bordering the Mediterranean . The Alps—including the Julian Alps, the Kamnik-Savinja Alps and the Karavanke chain, as well as the Pohorje massif—dominate Northern Slovenia along its long border with Austria. Slovenia's Adriatic coastline stretches approximately 47 km (29 mi)[13] from Italy to Croatia. The term "Karst topography" refers to that of southwestern Slovenia's Kras Plateau, a limestone region of underground rivers, gorges, and caves, between Ljubljana and the Mediterranean. On the Pannonian plain to the East and Northeast, toward the Croatian and Hungarian borders, the landscape is essentially flat. However, the majority of Slovenian terrain is hilly or mountainous, with around 90% of the surface 200 m (656 ft) or more above sea level.

Four major European geographic regions meet in Slovenia: the Alps, the Dinarides, the Pannonian Plain, and the Mediterranean. Slovenia's highest peak is Triglav (2,864 m/9,396 ft); the country's average height above sea level is 557 m (1,827 ft). Although on the shore of the Adriatic Sea, near the Mediterranean, most of Slovenia is in the Black Sea drainage basin. The geographical centre of Slovenia is at the coordinates 46°07'11.8" N and 14°48'55.2" E. It lies in Spodnja Slivna near Vače in the municipality of Litija. Slovenia's coastline measures 47 km (29 mi).

Around half of the country (11,691 km2/4,514 sq mi) is covered by forests; the third most forested country in Europe, after Finland and Sweden. Remnants of primeval forests are still to be found, the largest in the Kočevje area. Grassland covers 5,593 km2 (2,159 sq mi) and fields and gardens (954 km2/368 sq mi). There are 363 km2 (140 sq mi) of orchards and 216 km2 (83 sq mi) of vineyards. There is a Continental climate in the northeast, a severe Alpine climate in the high mountain regions, and a sub-Mediterranean climate in the coastal region. Yet there is a strong interaction between these three climatic systems across most of the country. This variety is also reflected in climatic variability over time and is an important factor determining the impact of global climate change in the country.

Natural regions

The first regionalisations of Slovenia were made by geographers Anton Melik (1935–1936) and Svetozar Ilešič (1968). The newer regionalisation by Ivan Gams divides Slovenia in the following macroregions:

- the Alps (visokogorske Alpe)

- the Prealpine Hills (predalpsko hribovje)

- the Ljubljana Basin (Ljubljanska kotlina)

- Submediterranean (Littoral) Slovenia (submediteranska - primorska Slovenija)

- the Dinaric Karst of inner Slovenia (dinarski kras notranje Slovenije)

- Subpannonian Slovenia (subpanonska Slovenija)

According to a newer natural geographic regionalisation, the country consists of four macroregions. These are the Alpine, the Mediterranean, the Dinaric, and the Pannonian landscapes. Macroregions are defined according to major relief units (the Alps, the Pannonian plain, the Dinaric mountains) and climate types (submediterranean, temperate continental, mountain climate).[14] These are often quite interwoven.

Protected areas of Slovenia include national parks, regional parks, and nature parks. Under the Wild Birds Directive, 26 sites totalling roughly 25% of the nation's land are "Special Protected Areas"; the Natura 2000 proposal would increase the totals to 260 sites and 32% of national territory.

Biodiversity

Although Slovenia is a small country, there is an exceptionally wide variety of habitats. In the north of Slovenia are the Alps (namely, Julian Alps, Karavanke, Kamnik Alps), and in the south stand the Dinaric Alps. There is also a small area of the Pannonian plain and a Littoral Region. Much of southwestern Slovenia is characterised by Classical Karst, a very rich, often unexplored underground habitat containing diverse flora and fauna.

About 54% of the country is covered by forests.[15] The forests are an important natural resource, but logging is kept to a minimum, as Slovenians also value their forests for the preservation of natural diversity, for enriching the soil and cleansing the water and air, for the social and economic benefits of recreation and tourism, and for the natural beauty they give to the Slovenian landscape. In the interior of the country are typical Central European forests, predominantly oak and beech. In the mountains, spruce, fir, and pine are more common. The tree line is at 1,700 to 1,800 metres (or 5,575 to 5,900 ft).

Pine trees also grow on the Kras plateau. Only one third of Kras is now covered by pine forest. Before that Kras was covered by oak forest. It is said that most of the forest was chopped down long ago to provide the wooden piles on which the city of Venice now stands. The Kras and White Carniola are known for the proteus. The lime/linden tree, also common in Slovenian forests, is a national symbol.

In the Alps, flowers such as Daphne blagayana, various gentians (Gentiana clusii, Gentiana froelichi), Primula auricula, edelweiss (the symbol of Slovene mountaineering), Cypripedium calceolus, Fritillaria meleagris (snake's head fritillary), and Pulsatilla grandis are found.

The country's fauna includes marmots, Alpine ibex, and chamois. There are numerous deer, roe deer, boar, and hares. The edible dormouse is often found in the Slovenian beech forests. Hunting these animals is a long tradition and is well described in the book The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola (Slovene: Slava vojvodine Kranjske, 1689), written by Janez Vajkard Valvasor (1641–1693). Some important carnivores include the Eurasian lynx (reintroduced to the Kočevje area in 1973), European wild cats, foxes (especially the red fox), and European jackal.[16] There are also hedgehogs, martens, and snakes such as vipers and grass snakes. As of March 2005, Slovenia also has a limited population of wolves and around four hundred brown bears.

There is a wide variety of birds, such as the Tawny Owl, the Long-eared Owl, the Eagle Owl, hawks, and Short-toed Eagles. Various other birds of prey have been recorded, as well as a growing number of ravens, crows and magpies migrating into Ljubljana and Maribor where they thrive. Other birds include (both Black and Green) Woodpeckers and the White Stork, which nests in Prekmurje. The marble trout or marmorata (Salmo marmoratus) is an indigenous Slovenian fish. Extensive breeding programmes have been introduced to repopulate the marble trout into lakes and streams invaded by non-indigenous species of trout.

The only regular species of cetaceans found in the northern Adriatic sea is the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus).[17]

Domestic animals originating in Slovenia include the Carniolan honeybee, the indigenous Karst Shepherd and the Lipizzan horse. The exploration of various cave systems has yielded discoveries of many cave-dwelling insects and other organisms.

Slovenia is a veritable cornucopia of forest, cavern and mountain-dwelling wildlife. Many species that are endangered or can no longer be found in other parts of Europe can still be found here.

Economy

Slovenia has a high-income developed economy which enjoys the highest GDP per capita of the new member states in the European Union, at $29,521 in 2008,[18] or 91% of the EU average.[19] Slovenia today is a developed country that enjoys prosperity and stability, as well as a GDP per capita substantially higher than that of the other transitioning economies of Central Europe. In 2009, it had a GDP (PPP) per capita of 27,654 International dollars, which is approximately the same level of South Korea and New Zealand. Slovenia benefits from a well-educated and productive work force, and its political and economic institutions are vigorous and effective.

There is however a big difference in prosperity between Western Slovenia (Ljubljana, the Slovenian Littoral and Upper Carniola) with a GDP per capita at 106,7% of the EU average, which at the level or certain prosperous European areas such as East Flanders, Outer London or Alsace, and South Eastern Slovenia (Inner Carniola, Lower Carniola, Slovenian Styria, Slovenian Carinthia and Prekmurje) which has a GDP per capita at 72.5% of the EU average, comparable to the poorest regions of Spain or Italy, such as Extremadura or Basilicata.

Although Slovenia has taken a cautious, deliberate approach to economic management and reform, with heavy emphasis on achieving consensus before proceeding, its overall record is one of success. Slovenia's trade is oriented towards other EU countries, mainly Germany, Austria, Italy, and France. This is the result of a wholesale reorientation of trade toward the West and the growing markets of central and eastern Europe in the face of the collapse of its Yugoslav markets. Slovenia's economy is highly dependent on foreign trade.

Trade equals about 120 % of GDP (exports and imports combined). About two-thirds of Slovenia's trade is with EU members.This high level of openness makes it extremely sensitive to economic conditions in its main trading partners and changes in its international price competitiveness. However, despite the economic slowdown in Europe in 2001–03, Slovenia maintained 3% GDP growth. Keeping labour costs in line with productivity is thus a key challenge for Slovenia's economic well-being, and Slovenian firms have responded by specialising in mid- to high-tech manufacturing. Industry and construction comprise over one-third of GDP. As in most industrial economies, services make up an increasing share of output (57.1%), notably in financial services.

A big portion of the economy remains in state hands and foreign direct investment (FDI) in Slovenia is one of the lowest in the EU per capita. Taxes are relatively high, the labor market is seen by business interests as being inflexible, and industries are losing sales to China, India, and elsewhere.[20] Unemployment used to be relatively low, but it rose to 5.5% in 2009 and to 8,4% in 2010.[21]

During the 2000s, privatisations were seen in the banking, telecommunications, and public utility sectors. Restrictions on foreign investment are being dismantled, and foreign direct investment (FDI) is expected to increase. Slovenia is the economic front-runner of the countries that joined the European Union in 2004, was the first new member which adopted the euro on 1 January 2007 and held the presidency of the European Union in the first half of 2008.

In the late 2000s economic crisis, Slovenian economy suffered a severe setback. In 2009, the Slovenian GDP per capita shrunk by -7.33 %, which was the biggest fall in the European Union after the Baltic countries and Finland. Unemployment rose from 5,1% in 2008 to 8,4% in 2010.,[22] which is still under the average in the European Union. However, Slovenia has a relatively small public debt and stable public finance. The expected GDP growth in 2010 is of -0,1%.

Transport

Railways

Slovenian Railways operates 1,229 km of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge tracks, 331 km as double track, and reaches all regions of the country. It is well connected to every surrounding country reflecting the fact that Slovenia used to be part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and later of Yugoslavia.

Electrification is provided by a 3 kV DC system and covers about 503 km. The remainder of the former Yugoslavian railroads that have been electrified operate with 25 kV AC system, thus trains to Zagreb will be switching engines at Dobova until dual system engines are available.

Highways

The first highway in Slovenia, the A1, was opened in 1970, connecting Vrhnika and Postojna. Constructed under the reformist minded Communist government of Stane Kavčič, their development plan envisioned a modern highway network spanning Slovenia and connecting the republic to Italy and Austria. After the reformist fraction of the Communist Party of Slovenia was deposed in the early 1970s, the expansion of the Slovenian highway network came to a halt.

In the 90s the new country started the 'National Programme of Highway Construction', effectively re-using the old Communist plans. Since then about 400 km of motorways, expressways and similar roads have been completed, easing automotive transport across the country and providing a much better road service between eastern and western Europe. This has provide a boost to the national economy, encouraging the development of transportation and export industries.

There are two types of highways in Slovenia. Avtocesta (abbr. AC) are dual carriageway motorways with a speed limit of 130 km/h. They have green road signs as in Italy, Croatia and other countries nearby. A hitra cesta (HC), or "fast road", is a secondary road, also a dual carriageway, but without an emergency lane. They have a speed limit of 100 km/h and have blue road signs.

Since the 1st June 2008 highway users in Slovenia are required to buy a vignette. 7-day, 1-month and 12-month passes are available.

As of 2008 159 km of Highway is under construction in Slovenia. Out of this total 94 km shall be opened during the year and work shall begin upon a further 10 km.

Ports and harbours

Until the end of World War I the main Austrian imperial port of Trieste (Slovene: Trst, German: Triest) was the main port in Slovenia. As the city stood surrounded by territory inhabited by Slovenes and its population being a third Slovene, it was hoped that it would, based on Wilson's 14 points, form a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. But after the city fell to Italy and remained under Italy after World War II which was finalised in the London Memorandum of Understanding of 1954 the Slovenian government saw the need for a new port.

Thus the Port of Koper was established in 1957 and opened to international trade in 1958. The port has since been much expanded, and in 2007 more than 15 million tonnes of cargo passed through it, making it the second biggest port in the North Eastern Adriatic after Trieste and before Rijeka. Further development and expansion of the port in Koper now depends largely on the construction of the third pier and on the opening of a second rail track between Koper and the Slovene rail network to ease the transport of goods from the port to the rest of Slovenia and Europe. This work still needs to be announced by the national government and local authorities, with whom the provision of these new facilities largely rests.

Airports

Slovenia has three significant international airports. Ljubljana Jože Pučnik Airport is by far the busiest airport in the country with connections to many major European destinations. More than 1.5 million passengers and 22,000 tonnes of cargo pass through the airport each year. The second largest international airport is the Maribor Edvard Rusjan Airport. However, this airport has struggled since Slovenian independence due to negative economic changes that affected the Maribor region. Only 30,000 passengers passed through in 2007. Portorož Airport, located near Sečovlje on the Slovene coast, close to the resort town of Portorož, serves only small private aircraft. Slovenia also has an active Air Force Base in Cerklje ob Krki Air Base.

Communications

The use of internet in Slovenia is widespread; according to official polls in the first quarter of 2008, 58% citizens between the ages 10 and 74 were internet users, which is above Europe's average. In the same period, 59% households (85% of which through broadband) and 97% companies with 10 or more employed (84% of those through broadband) had internet access. The country's top-level domain is .si. It is administered by ARNES, the Academic and Research Network of Slovenia. Other major providers are Telekom Slovenije (under the trademark SiOL), Telemach, AMIS and T-2. Slovenian internet service providers provide ADSL; ITU G.992.5, VDSL, SHDSL, VDSL2 and FTTH.

Demographics

Slovenia's main ethnic group is Slovene (83%). Ethnic groups from other parts of the former Yugoslavia (Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Macedonian, Montenegrin and people who consider themselves "Yugoslavian") form 5.3%, and the Hungarian, Albanian, Roma, Italian and other minorities form 2.8% of the population. Ethnic affiliation of 8.9% was either undeclared or unknown.

Life expectancy in 2007 was 74.6 years for men and 81.8 years for women.[23] The suicide rate is 19.8 per 100,000 persons per year.[24]

With 99 inhabitants per square kilometre (256/sq mi), Slovenia ranks low among the European countries in population density (compared to 320/km² (829/sq mi) for the Netherlands or 195/km² (505/sq mi) for Italy). The Notranjska-Kras statistical region has the lowest population density while the Central Slovenian statistical region has the highest. Approximately 51% of the population lives in urban areas and 49% in rural areas.

The official language is Slovene, which is a member of the South Slavic language group. Hungarian and Italian enjoy the status of official languages in the ethnically mixed regions along the Hungarian and Italian borders.

Many Slovenes are multilingual. According to the Eurobarometer survey[25], the majority of Slovenes can speak Croatian and English. 45% of population can speak German in addition to Slovene. After the Netherlands and Denmark, Slovenia is the country with the highest percentage of German speakers outside German speaking countries. Italian is widely spoken (for historical and geographical reasons) on the Slovenian Coast and in other border areas of the Slovenian Littoral; around 13% of Slovenians can speak Italian, which is the highest percentage in the European Union after Italy and Malta.

Traditionally, Slovenes are Roman Catholic (57.8% according to the 2002 Census) but like elsewhere in Europe the Roman Catholicism affiliation in Slovenia is dropping (71.6% according to the 1991 census), a drop of more than 1 % annually.[26]

According to the more recent but 5 year old Eurobarometer Poll 2005,[27] 37% of Slovenian citizens responded that "they believe there is a god", whereas 46% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 16% that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, god, or life force".

Culture

Slovenia's first book was printed by the Protestant reformer Primož Trubar (1508–1586). It was actually two books, Latin: Catechismus (a catechism) and Abecedarium, which were published in 1550 in Tübingen, Germany.

The central part of the country, namely Carniola (which existed as a part of Austria-Hungary until the early 20th century) was ethnographically and historically well-described in the book The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola (German: Die Ehre deß Herzogthums Crain, Slovene: Slava vojvodine Kranjske), published in 1689 by Baron Janez Vajkard Valvasor (1641–1693).

Some of Slovenia's greatest authors were the poets France Prešeren (1800–1849), Oton Župančič, Srečko Kosovel, Edvard Kocbek and Dane Zajc, as well as the writer and playwright Ivan Cankar (1876–1918). Boris Pahor, Evald Flisar, Drago Jančar, Alojz Rebula, Tomaž Šalamun and Aleš Debeljak are some of the leading names of contemporary Slovene literature.

The most important Slovene painters include Jurij Šubic and Anton Ažbe in late 19th century. Ivana Kobilca, Rihard Jakopič, Ivan Grohar worked in the beginning of 20th century while Avgust Černigoj, Lojze Spacal, Anton Gojmir Kos, Riko Debenjak, Marij Pregelj, exceptional Gabrijel Stupica, Janez Bernik worked mostly in the second part of 20. century. Contemporary artists are Emerik Bernard, Metka Krašovec, Ivo Prančič, Gustav Gnamuš, group IRWIN and Marko Peljhan. Zoran Mušič, who worked in Paris and Venice, obtained world fame.

Some important Slovene sculptors were Fran Berneker, Lojze Dolinar, Zdenko Kalin, Slavko Tihec, Janez Boljka and now Jakov Brdar and Mirsad Begić. The most famed Slovene architects were Jože Plečnik and Max Fabiani and later Edo Ravnikar and Milan Mihelič.

Slovenia is a homeland of numerous musicians and composers, including Renaissance composer Jacobus Gallus (1550–1591), who greatly influenced Central European classical music, and the violin virtuoso Giuseppe Tartini. In the twentieth century, Bojan Adamič was a renowned film music composer and Ivo Petrić (born 16 June 1931) is a composer of European classical music.

Contemporary popular musicians have been Slavko Avsenik, Laibach, Vlado Kreslin, Pero Lovšin, Pankrti, Zoran Predin, Lačni Franz, New Swing Quartet, DJ Umek, Valentino Kanzyani, Siddharta, Big Foot Mama, Terrafolk, Katalena, Magnifico and others.

Slovene cinema has more than a century-long tradition with Karol Grossmann, Janko Ravnik, Ferdo Delak, France Štiglic, Mirko Grobler, Igor Pretnar, France Kosmač, Jože Pogačnik, Matjaž Klopčič, Jane Kavčič, Jože Gale, Boštjan Hladnik and Karpo Godina as its most established filmmakers. Contemporary film directors Janez Burger, Jan Cvitkovič, Damjan Kozole, Janez Lapajne and Maja Weiss are the most notable representatives of the so-called "Renaissance of Slovenian cinema".

Famous Slovene scholars include the chemist and Nobel prize laureate Friderik - Fritz Pregl, physicist Joseph Stefan, psychologist and anthropologist Anton Trstenjak, philosophers Slavoj Žižek and Milan Komar, linguist Franc Miklošič, physician Anton Marko Plenčič, mathematician Jurij Vega, sociologist Thomas Luckmann, theologian Anton Strle and rocket engineer Herman Potočnik.

Sport

A variety of other sports are played in Slovenia on professional level, with important international successes in handball, basketball, volleyball, association football, ice hockey, rowing, swimming, and athletics.

Prior to World War Two, gymnastics and fencing used to be the most popular sports in Slovenia, with champions like Leon Štukelj, Miroslav Cerar, Rudolf Cvetko and Richard Verderber gaining Olympic medals for Austria-Hungary and Yugoslavia. Gymnastics has a long tradition, as it was first popularized in the mid 19th century by the influential gymnastic Sokol and Orel associations, which were not only sporting associations but also political and cultural movements. Association football gained popularity in the interwar period. After 1945, basketball, handball and volleyball became increasingly popular among Slovenes, and from the mid 1970s onward, winter sports. Until recently, all those sports were more popular than association football, which enjoyed a dubious social status, frequently associated with lower classes and immigrants from other areas of former Yugoslavia. Since the first major successes of the Slovenia national football team in the early 2000s, football has become increasingly popular, as well.

Football in Slovenia is played domestically at the top level in the Slovenian PrvaLiga (1. SNL), with 10 teams. Followed by the 2.SNL, and the two-sectioned 3.SNL. The Slovenia national football team, is ranked 19 in the world and has qualified for 2 FIFA World Cup's (2002, 2010), and 1 UEFA European Football Championship (2000), in the past decade. The national team qualified for the 2010 FIFA World Cup by upsetting heavily favoured Russia in the qualifying tournament's play-off stage. They came 3rd in their group following a loss to England in the Group C. Slovene past and current football stars include Srečko Katanec, Zlatko Zahovič, Robert Koren, Milivoje Novakovič, and Zlatan Ljubijankič.

Top-level Slovene Basketball is played in the Premier A Slovenian Basketball League, with 13 teams. The Slovenian national basketball team has qualified for 8 Eurobaskets, including a 4th place finish in 2009, and 2 FIBA World Championship appearances in 2006 and 2010. Famous Slovene basketball players who have played in the NBA include Marko Milič, Goran Dragić, Sasha Vujačić, Radoslav Nesterović, and Beno Udrih.

The Slovenian Ice Hockey Championship, with 10 teams, is the highest level ice hockey league in the country. The Slovenia men's national ice hockey team is currently ranked 17 in the world, and has qualified for 5 Ice Hockey World Championships. One of Slovenia's most famous athletes is Anže Kopitar who plays for the Los Angeles Kings of the National Hockey League, and his USD $47.6 million (€34.7 million) 7-year contract, is the greatest amount by any Slovene athlete. Other famous Slovene hockey players include; Robert Kristan, Jan Muršak, and Marcel Rodman.

Winter sports are among the most popular sport events in Slovenia. Past and current Slovenian Alpine ski champions include Mateja Svet, Bojan Križaj, Jure Franko, Rok Petrovič, Jure Košir, and Tina Maze. Ski jumping is also very popular, with champions like Franci Petek, Primož Ulaga, Primož Peterka and Peter Žonta.

Individual sports are also very popular in Slovenia, and have been traditionally considered more characteristically Slovenian than team sports. Mountaineering is one of the most widespread sporting activities in Slovenia. Many Slovene mountaineers have gained an international reputation, including Tomo Česen, Davo Karničar and Tomaž Humar. The tradition of Slovene mountaineering is on display in the Slovenian Alpine Museum in Mojstrana. Many Slovenians are active in extreme sports; probably the most famous of them being the marathon swimmer Martin Strel.

Education

The Slovenian education system consists of:

- pre-school education

- basic education (single structure of primary and lower secondary education)

- (upper) secondary education: vocational and technical education, secondary general education

- higher vocational education

- higher education

Specific parts of the system:

- adult education

- music and dance education

- special needs education

- programmes in ethnically and linguistically mixed areas

Currently there are three public universities in Slovenia:

- University of Ljubljana

- University of Maribor

- University of Primorska

In addition, there is the private University of Nova Gorica.

The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Slovenia's education as the 12th best in the world and 4th best in the European Union, being significantly higher than the OECD average.[28]

Primary school

Children first enter primary schooling at about the age of 6 and finish at about the age of 14 (9 school years). Each group of children born in the same year form one grade or class in primary school which lasts until the end of primary school. Each grade or year is divided into 2 terms. Once or twice per term, children have holidays: Autumn, Christmas, winter and May first holidays; each holiday is approximately one week long. At summer time, school ends on 24 June (except in the last/ninth grade, where it ends one week earlier), followed by a holiday of more than two months. The next school year starts on the 1 September.

Cuisine

There is no such thing as a single, uniform, distinct Slovenian cuisine. There are more than 40 distinct regional cuisines in a country whose main distinguishing feature is a great variety and diversity of land formation, climate, wind movements, humidity, terrain and history.

Slovenian cuisine is a mixture of three great regional cuisines, the Central European cuisine (especially Austrian and Hungarian), the Mediterranean cuisine and the Balkan cuisine.

Historically, Slovenian cuisine was divided into town, farmhouse, cottage, castle, parsonage and monastic cuisine. The first Slovenian cookbook was published in Slovenian language by Valentin Vodnik in 1799. Soups are a relatively recent invention in Slovenian cuisine, but there are over 100. Earlier there were various kinds of porridge, stew and one-pot meals. The most common meat soups are beef and chicken soup. Meat-based soups are served only on Sundays and feast days; more frequently in more prosperous country or city households.

There is a variety of sausages in the Slovenian cuisine, the most famous of which is Kranjska klobasa, also known in English as Kransky.

Honey is used to a considerable extent. Medenjaki, which come in different shapes are honey cakes, which are most commonly heart-shaped and are often used as gifts.

Slovenian national dishes are Bujta repa, Ričet, Prekmurska gibanica, Potica, Jota, Mineštra, Pršut, Kranjska klobasa and Žlikrofi.

International rankings

| Organization | Survey | Ranking |

|---|---|---|